Published by: Diana Luai Awad, Dr Pharmacist

The new Rome IV Criteria for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders were introduced at a regular American Digestive Disease Week in San Diego in May 2016. They include the criteria for one of the most common functional diseases — irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)1.

10 to 13% of the population suffer from IBS. The number of people experiencing symptoms of IBS is likely to be higher, but only 25-30% of them seek medical help. IBS is more common in women, with most cases being diagnosed between the ages of 30 and 50. According to the latest clinical guidelines "Irritable Bowel Syndrome" published in 2021, the disease is accompanied by functional dyspepsia in the majority of patients with IBS (13-87%).

Having IBS is not associated with higher risk of colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease or higher mortality. Nevertheless, the disease can impair patients quality of life dramatically2 and leads to significant direct and indirect costs for its treatment and diagnosis3.

Etiology and pathogenesis

Pathogenesis of IBS is quite complex and has not been studied sufficiently to formulate a universal hypothesis that could explain the nature of this disease. Violation of the structure and function of the intestinal mucosal epithelial barrier is considered to be one of the alleged links of pathogenesis. The causes are:

- • genetic polymorphism;

- • acute intestinal infections;

- • antibiotic therapy;

- • changes in the microbiota composition;

- • psychological or emotional stress;

- • diet4.

Changes in the microbiota accompanied by mucosal epithelial barrier dysfunction lead to inflammatory changes in the intestinal wall. Chronic inflammation disrupts visceral sensitivity, which leads to higher nerve centers (especially the limbic system) hyperactivation, along with increased efferent intestine innervation. This results in intestinal smooth muscles spasms and IBS symptom complex formation. Concomitant emotional disorders (anxiety, depression, somatization) contribute to a "vicious circle", in which the patient focuses on somatic symptoms, which intensifies them4.

IBS classification

Depending on the nature of the stool changes, there are four types of IBS. This classification is based on the stool shape according to the Bristol scale, which is understood by patients easily and allows you to identify the nature of stool disorders quickly4.

Table 1. Bristol stool scale

|

Type 1 |

Separate hard lumps (like nuts) |

|

Type 2 |

Normal sausage-shaped, but with hard lumps |

|

Type 3 |

Normal sausage-shaped, but with deep cracks on its surface |

|

Type 4 |

Normal sausage-shaped or snake-shaped, with a smooth surface and soft texture |

|

Type 5 |

Ball-shaped with clear cut edges, evacuate easily |

|

Type 6 |

With ragged edges, mushy |

|

Type 7 |

Watery or loose stools without hard lumps |

Table 2. Types of IBS based on the Bristol stool scale

|

|

Type |

Symptoms |

Alternative Diagnosis |

|

1 |

IBS with constipation (IBS-C) |

More than 25% of bowel movements are Bristol stool scale types 1-2, less than 25% are types 6-7 |

The patient reports predominantly constipation (Bristol stool scale types 1-2) |

|

2 |

IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D) |

More than 25% of bowel movements are Bristol stool scale types 6-7, less than 25% are types 1-2 |

The patient reports predominantly diarrhea (Bristol stool scale types 6-7) |

|

3 |

Mixed IBS (IBS-M) |

More than 25% of bowel movements are Bristol stool scale types 1-2 and more than 25% are types 6-7 |

The patient reports constipation (more than ¼ of all bowel movements) and diarrhea (more than ¼ of all bowel movements), which corresponds to Bristol stool scale types 1-2 and 6-7 |

|

4 |

Unclassified IBS (IBS-U) |

The patient's complaints meet IBS diagnostic criteria, but are not sufficient to diagnose the first three types of the disease |

|

Complaints and anamnesis

Basically, patients with IBS complaints can be divided into three types:

- intestinal;

- related to other parts of the digestive system (eg, nausea, heartburn);

- non-gastroenterological (dyspareunia, sense of incomplete bladder emptying, fibromyalgia, migraine).

Let us consider patients with IBS complaints in more detail:

Stomach ache

- the patient may describe the pain as indefinite, burning, dull, aching, constant, stabbing, twisting;

- pain in the iliac regions mainly, more often on the left. The pain usually intensifies after eating and remits after defecation, passing gases, taking antispasmodic drugs;

- in women, the pain increases during menstruation. Pain relief at night is an important distinctive feature of IBS pain syndrome. Transient pain is more common than persistent pain.

Bloating

- less noticeable in the morning;

- increases during the day;

- gets aggravated after eating.

Constipation and/or diarrhea

- diarrhea usually occurs in the morning after breakfast, the frequency of bowel movements varies from 2 to 4 or more in a short period of time, diarrhea is often accompanied by imperative urges and a feeling of incomplete intestine emptying;

- stool is often denser during the first act of defecation during following ones, when the volume of intestinal contents is less, but the stool consistency is more liquid;

- stool output per day does not exceed 200 g. No diarrhea at night;

- with constipation, hard lumps, like nuts, pencil-thin stool, as well as stool with ragged edges (dense, formed stool at the beginning of defecation, and then mushy or even watery stool) are possible;

- the stool does not contain blood and pus impurities, however, excess mucus is often present.

Carefully evaluate if the patient understands the terms "constipation" and "diarrhea" correctly. Patients with IBS often complain about diarrhea, meaning frequent defecation, in which the stool remains formed; and patients with “constipation” sometimes mean anorectal discomfort during bowel movements, infrequent or dense stools4.

Complaints not related to bowel movement

- dyspepsia (present in 15-45% of patients with IBS), nausea, heartburn;

- pain in the lumbar region, other muscle and joint pain;

- urological symptoms (nocturia, frequent and imperative urge to urinate, feeling of incomplete bladder emptying);

- dyspareunia (pain in women during intercourse);

- night sleep disorder.

Anxiety symptoms

The symptoms below may testify of organic pathology and should indicate need in in-depth examination:

- weight loss;

- old age of disease onset;

- nocturnal symptoms;

- Colon cancer, celiac disease, ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease in relatives;

- constant abdominal pain as the only gastrointestinal symptom;

- progressive course of the disease.

- fever;

- changes in the internal organs (hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, etc.).

Laboratory tests

- hemoglobin level decrease;

- leukocytosis;

- high ESR;

- occult blood in the stool;

- changes in the biochemical analysis of blood;

- steatorrhea and polyfecalia.

IBS diagnosis

As with other gastrointestinal disorders, IBS diagnosis can be done based on the patient's symptoms correspondence with the Rome IV criteria, absent organic gastrointestinal pathology that could explain the symptoms. According to these criteria, IBS is defined as a functional bowel disorder accompanied by recurrent abdominal pain that occurs at least once a week and is related to two or more of the following:

- Bowel movements

- Change in the frequency of bowel movements

- Change in the shape (appearance) of the stool

These signs should be noticed in the patient for the last 3 months with a total duration of at least 6 months5. When diagnosising, it is necessary to indicate the type of predominant stool shape changes (see classification above). Four diagnosis types are possible (IBS with diarrhea, IBS with constipation, IBS mixed variant, IBS, unclassified variant).

The following laboratory tests are necessary for diagnosis:

Table 3. Essential laboratory tests

|

Type of test |

Purpose |

Multiplicity |

|

Basic blood test |

Screen |

Once |

|

Basic urine test |

Screen |

Once |

|

Stool test |

Screen |

Once |

|

Stool bacteria test |

Exclude acute intestinal infections |

Once |

|

Fecal occult blood test |

Differential diagnosis of inflammatory bowel diseases and colorectal cancer |

Once |

|

Basic stool test |

Screen |

Once |

|

Stool OVA and Parasites test |

Exclude helminthiasis |

Once |

|

Total blood bilirubin, AST, ALT, alkaline phosphatase, GTP, total protein, creatinine |

Exclude coexisting liver disease |

Once |

|

HBV and HCV antibody test |

Exclude viral hepatitis |

Once |

|

HIV and AIDS blood test |

Exclude specific gastrointestinal diseases |

Once |

Table 4. Additional laboratory tests

|

Type of test |

Purpose |

Multiplicity |

|

Fecal calprotectin |

Exclude inflammatory intestinal deseases |

Once |

|

Clostridium difficile toxin A/B test |

Exclude clostridial infection |

Once |

|

Tissue Transglutaminase Antibodies (tTG-IgA, IgB) |

Exclude celiac disease |

Once |

|

Immunoglobulin A (IgA), Immunoglobulin B (IgB) test |

Exclude celiac disease |

Once |

|

Antibody titers to intestinal infections (shigellosis, salmonellosis, yersiniosis, campylobacter) tests |

Identify gastrointestinal infection markers |

Once |

|

Stool pathogen PCR test (shigella, salmonella, yersinia, campylobacter) |

Exclude acute intestinal infection |

Once |

|

Enterovirus, norovirus, astrovirus, rotavirus stool PCR test |

Exclude viral diarrhea |

Once |

|

Giardia lamblia IgG, IgA, IgM antibody test |

Exclude giardiasis |

Once |

|

Chromogranin A (CgA), gastrin, serotonin, acetylcholine blood test |

Exclude neuroendocrine tumor |

Once |

|

Immunoglobulins (IgA, IgG, IgM) blood test |

Exclude immunodeficiency diseases |

Once |

|

Thyroid Function Tests |

Exclude thyroid disease |

Once |

Table 5. Essential imaging methods

|

Type of test |

Purpose |

Multiplicity |

|

Sigmoidoscopy |

Exclude ulcerative colitis, rectal tumor |

Once |

|

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy with duodenal mucosal biopsy |

Exclude celiac disease, Whipple's disease, eosinophilic enteritis, amyloidosis |

Once |

|

Colonoscopy with examination of the distal ileum and colon mucosa biopsy |

Exclude Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, colon tumor, diverticular disease |

Once |

|

Irrigoscopy |

Exclude colon tumor, diverticular disease |

Once |

|

An abdominal ultrasound |

Exclude liver, gallbladder, pancreas diseases |

Once |

Table 6. Essential imaging methods

|

Type of test |

Purpose |

Multiplicity |

|

Stomach and small intestine X-ray |

Exclude Crohn's disease, small bowel tumor |

Once |

|

Defecography |

Exclude rectocele |

Once |

|

Doppler sonography of the abdominal vessels |

Exclude abdominal ischemia syndrome |

Once |

|

Sphincterometry |

Exclude rectum sphincters disorders with constipation |

Once |

|

Balloon dilatation |

Visceral sensitivity in IBS |

Once |

|

Electromyography of the pelvic floor muscles |

Diagnosis |

Once |

|

Anorectal manometry |

Diagnosis |

Once |

|

Abdomenal MRI |

Diagnosis |

Once |

|

CT enterography |

Exclude Crohn's disease, small bowel tumor |

Once |

|

Intestinal ultrasound |

Diagnosis |

Once |

|

Hydrogen breath test for lactose intolerance |

Excessive bacterial growth in the small intestine lumen, lactase deficiency diagnosis |

Once |

|

Lactulose hydrogen-methane breath test |

Excessive bacterial growth diagnosis |

Once |

|

Descending duodenum mucosa biopsy test |

Enteropathy with impaired membrane digestion (lactase and other disaccharidase deficiencies) |

Once |

Table 7. Additional expert advice

|

Expert |

Purpose |

Multiplicity |

|

Endocrinologist |

Thyrotoxicosis, hypothyroidism |

Once |

|

Gynecologist |

Gynecological diseases |

Once |

|

Urologist |

Prostatitis, prostate adenoma |

Once |

|

Infectious disease specialists |

Acute intestinal infections |

Once |

|

Psychoneurologist and psychotherapist |

Psychosomatic disorders |

Twice: before and after treatment |

|

Rheumatologist |

Myalgia |

Once |

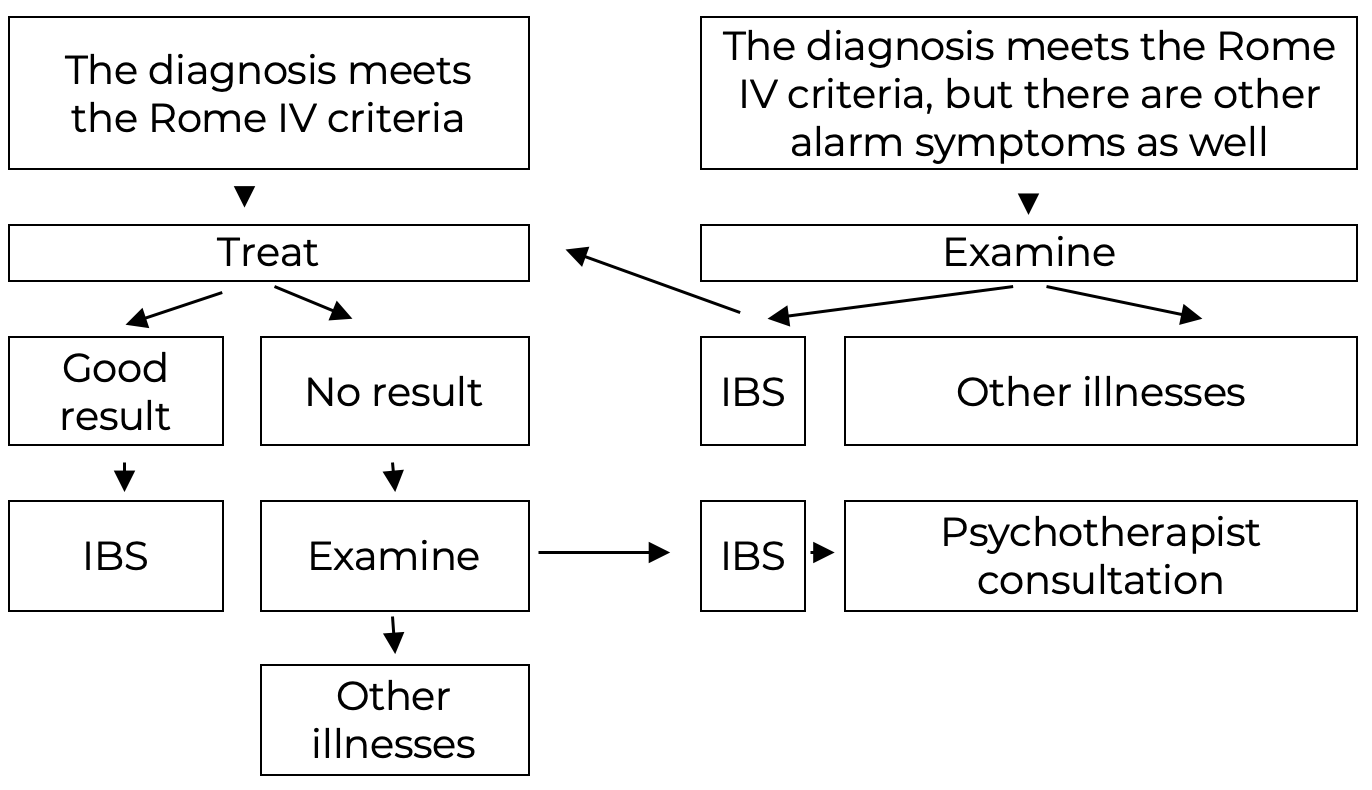

Scheme 1. IBS diagnosis algorithm:

IBS treatment

Treatment is complex. The effectiveness of drugs that normalize intestinal motility, affect visceral sensitivity, or affect both mechanisms has been confirmed. Drugs that reduce inflammatory changes in the intestinal wall in this category of patients are being studied and have not been widely used yet. The complex of measures aimed at IBS treatment includes:

- Diet and lifestyle changes

- Pain relief drugs

- Diarrhea relief drugs

- Constipation relief drugs

- Probiotics

- Psychotropic drugs

The diet for IBS patients is selected individually via excluding foods that exacerbate symptoms (elimination diet). All IBS patients should be advised to:

- eat regularly at specially allotted times, avoid eating in a hurry, while working;

- do not skip meals and do not allow long breaks between them;

- in IBS-D (IBS and diarrhea) and IBS-M (mixed version of IBS) gluten-free diet can be prescribed, as well as low in oligodi- and oligomonosaccharides (lactose, fructose, fructans, galactans) and polyols (sorbitol, xylitol , mannitol) diets;

- if the diet is not effective enough, alpha-galactosidase can be prescribed (1-3 tablets with the first portions of food);

- keepe a "food diary" to identify foods that lead to the disease symptoms aggravation.

FODMAP carbohydrates limitation has been shown in various studies to be beneficial in IBS and other functional gastrointestinal diseases8,9. The abbreviation FODMAP stands for "Fermentable Oligo- (Oligo-), Di- (Di-), Mono- (Mono-) saccharides And (And) Polyols (Polyol)". A diet low in FODMAP carbohydrates was developed by Peter Gibson and Susan Shepherd at Monash University in Australia.

Table 8. List of low FODMAP foods to eat

|

Vegetables |

Carrots, cucumbers, peppers, egg-plants, lettuce, beans, potatoes, radishes, tomatoes, spinach, seaweed, zucchini, pumpkins |

|

Fruit |

Cranberries, blueberries, citrus fruit, bananas, kiwis, grapes, strawberries, nectarines, lemons |

|

Grains, cereals |

Corn, rice, buckwheat, oatmeal |

|

Meat |

Beef, veal, rabbit, lean lamb, mussels |

|

Poultry |

Chicken, turkey, quail |

|

Fish |

Low-fat fish (cod, hake, pollock, ice fish, perch, etc.) |

|

Drinks |

Tea, coffee, fruit drinks, home-made fruit and vegetable juice |

|

Dairy |

Hard cheeses (parmesan, cheddar, swiss cheese, etc.) Soft cheeses (brie, mozzarella, etc.) |

|

Milk alternatives |

Rice milk, almond milk, soy milk, lactose-free milk |

|

Oils and fat |

All vegetable oils and animal fats |

Table 9. List of high FODMAP foods to avoid

|

Vegetables |

Garlic, onions, artichoke, asparagus, avocado, beans, beetroot, Brussels sprouts, cauliflower, peas, green peppers, lentil, leek |

|

Fruit |

Apples, peaches, apricots, blackberry, cherry, sweet cherry, plumps (dried as well), watermelon |

|

Grains, cereals |

Products containing wheat, barley and rye, pasta, bran, cakes, semolina, butter biscuits |

|

Nuts |

Almonds, nuts, peanuts, cashew, chickpeas |

|

Products |

Processed fish and meat, canned poultry |

|

Drinks |

Canned fruit juice, drinks with glucose-fructose syrup, drinks with fructose syrup, drinks with other sweeteners, fruit juice, fizzy drinks, beer, rum, sweet wine, coconut vodka |

|

Sweets and sweeteners |

Fructose, glucose-fructose syrup, honey, isomalt, sorbitol, maltitol, mannitol, xylitol |

|

Dairy |

Cow and goat milk, yoghurts, cottage cheese, cream, ice-cream, milk serum |

Pain relief drugs

According to the Rome IV criteria, antispasmodics are recommended for abdominal pain treatment in IBS patients. The effectiveness of these drugs compared with placebo (58 and 46%, respectively) is described in a meta-analysis that includes 29 studies involving 2333 patients. The NNT indicator (the number of patients who need to be treated in order to achieve a positive result in one patient) with the use of antispasmodics was equal to 7.

Comparative evaluation of drugs showed high efficiency of hyoscine butylbromide and pinaverium bromide (NNT=3). In addition, according to the results of separate studies, the use of certain antispasmodics (for example, mebeverine), along with a decrease in abdominal pain intensity, leads to a significant improvement in the quality of life of patients with various types of IBS (romide, pirenzepine, propinox, scopolamine). Antispasmodics were proved to eliminate pain in IBS patients significantly more effectively compared with placebo (in 58 and 46% of patients, respectively, p < 0.001, NNT = 7)6. Mebeverine also has a high safety profile, patients tolerated it well with long-term use.

Medicines for diarrhea relief

IBS-D is treated with loperamide hydrochloride, dioctahedral smectite, non-absorbable antibiotic rifaximin, and probiotics. Loperamide hydrochloride improves stool consistency, reduces the number of urges to defecate by reducing the tone and motility of the intestinal smooth muscles, but does not affect other symptoms of IBS significantly, including abdominal pain. Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) comparing loperamide with other antidiarrheal agents have not been conducted.

Medications for constipation

Treatment of chronic constipation, including IBS-C, should begin with following general recommendations - increasing liquid volume in the patient's diet up to 1.5-2 liters per day and vegetable fiber, as well as increasing physical activity. However, the quality of studies evaluating these measures effectiveness was insufficient and stemmed from expert opinion based on individual clinical observations.

For IBS-C patints treatment, laxatives of the following groups are used:

- laxatives that increase the volume of stool (empty shells of psyllium seeds);

- osmotic laxatives (macrogol 4000, lactulose);

- laxatives that stimulate intestinal motility (bisacodyl).

If laxatives are inefficient, enterokinetic prucalopride can be prescribed.

Probiotics

Probiotics are live microorganisms that can be contained in a variety of foods, including medicines and dietary supplements, that have a beneficial effect on microflora function.

A meta-analysis published in 2009, which included 43 clinical studies that evaluated probiotics efficacy and safety, confirmed the positive effect of this group of drugs on the main IBS symptoms. Probiotics containing various strains of lactobacilli and bifidum bacteria effectiveness has been proven4.

A good quality probiotic must meet a number of requirements:

- the shell containing the probiotic should ensure its unimpeded passage through the intestines with subsequent delivery of bacterial cells to the intestine;

- a probiotic capsule or tablet must contain at least 1 billion (109) bacterial cells at the time of sale and must help kill pathogenic microorganisms in the gut without affecting beneficial bacteria adversely.

An alternative is preserving the viability of probiotics in the intestines and delivering microbial.

Psychotropic drugs

Publications of different years present data on central mechanisms of pain sensitivity and regulation of intestinal motility damage, concomitant mental and behavioral disorders from the groups of mood disorders, anxiety and somatoform disorders. Stress and past trauma are often significant factors in IBS.

This explains the interest in the group of psychopharmacological drugs with a wide range of pharmacodynamic effects of central and peripheral origin. Psychotropic drugs (tricyclic antidepressants - TCAs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors - SSRIs, antipsychotics) are used to correct emotional disorders diagnosed in most IBS patients with7, as well as to reduce the severity of abdominal pain8.

References:

- Lacy B.E., Mearin F., Lin Chang, et al. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2016; 150(6): 1393-407.

- El Serag HB, Olden K, Bjorkman D, El Serag HB, Olden K, and Bjorkman D. Health-related quality of life among persons with irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review, Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2002; 16(6): 1171 - 1185.

- Akehurst RL, Brazier JE, Mathers N, O’Keefe C, Kaltenthaler E, Morgan A, Platts M, and Walters SJ. Health-related quality of life and cost impact of irritable bowel syndrome in a UK primary care setting. Pharmacoeconomics. 2002; 20(7): 455 - 462.

- Clinical guidelines on irritable bowel syndrome (approved by the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation). 2021.

- Sheptulin A.A., Vize-Khripunova M.A.. Roman criteria for irritable bowel syndrome IV revision: are there any fundamental changes? Ros Journal Gastroenterol Hepatol Coloproctol. 2016; 26(5).

- Ruepert T., Quartero A.O., de Wit N.J. et al. Bulking agents, antispasmodics and antidepressants for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome (Review). Cochrain Library. 2013; 3: 1-120.

- Kibune-Nagasako, C., García-Montes, C., Silva-Lorena, S. L., & Aparecida-Mesquita, M. Irritable bowel syndrome subtypes: Clinical and psychological features, body mass index and comorbidities. Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas. 2016; 108(2), 59-64.

- Lacy, B. E., Mearin, F., Chang, L., Chey, W. D., Lembo, A. J., Simren, M., & Spiller, R. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016; 150(6): 1393-1407.

Colleagues, haven't you joined our PharmaCourses of MENA region Telegram chats yet?

In the chats of more than 6,000 participants, you can always discuss breaking news and difficult situations in a pharmacy or clinic with your colleagues. Places in the chats are limited, hurry up to get there.

Telegram chat for pharmacists of MENA region: https://t.me/joinchat/V1F38sTkrGnz8qHe

Telegram chat fo physicians of MENA region: https://t.me/joinchat/v_RlWGJw7LBhNGY0