Published by: Diana Luai Awad, Dr Pharmacist on Monday 04.July.2022

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is an acute, heterogeneous, immune-mediated disease of the peripheral nervous system. Its features are rapidly progressive symmetrical limb weakness with hyporeflexia or areflexia and sensory disturbances and cranial nerve deficits in some patients. It is the most common cause of acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) in the post-polio era. GBS was first described in 1916 by three French neurologists: Georges Guillain, Jean-Alexandre Barré and André Strol. It was diagnosed in two soldiers with an increased protein concentration and a normal CSF cell count. Haymaker and his colleagues described the clinical and pathological features of 50 GBS deaths and stated axonal degeneration, myelin destruction, and nerve edema in 1949. Thisby and his colleagues described a variant of GBS with direct axonal injury rather than demyelination in 19861. This variant was later called:

• acute motor axonal neuropathy (AMAN) if only motor axons were damaged

• acute motor sensory axonal neuropathy (AMSAN) if sensory axons were also affected.

Other clinical variants include:

• acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (AIDP)

• Miller Fisher syndrome (MFS) with the classic triad of areflexia, ataxia, and ophthalmoplegia.

There are less common variants of GBS, such as:

• pharyngeal-cervical-brachial one, which include the bibrachial variant and acute localized pharyngeal weakness, facial diplegia with paresthesia,

• acute pandysautonomy, sensory variant

• Bickerstaff brainstem encephalitis

• intersection syndrome2.

GBS is a kind of demyelinating polyneuropathy and is characterized by:

• symmetrical limb weakness

• hyporeflexia or rapidly progressive areflexia3.

Morbidity and causes

The disease is considered to be the most common cause of peripheral tetraparesis. The morbidity ranges from 1 to 2 cases per 100,000 population per year. Men are at a higher risk4,5. Aging increases the risk of the disease.

GBS is sometimes assumed to have a genetic predisposition with known triggers5,6:

• acute bacterial or viral infections

• helminthiases

• vaccination

• surgery.

Mostly, the patients indicate one or another provoking factor approximately 4 weeks before the onset of the first symptoms: from one week with the Zika virus, up to four-six with post-vaccination or a surgery. The disease is most often provoked by infections:

• campylobacter jejuni (35% of cases)

• cytomegalovirus (15%)

• Epstein-Barr virus (10%)

• mycoplasma pneumoniae (5%)

• influenza, varicella-zoster virus (Varicella zοster), Coxsackie, hepatitis E7 and other arboviruses, Haemophilus influenzae and helminthiases.

The literature describes cases of post-vaccination development of GBS that occurred after vaccination against influenza, rabies, diphtheria, whooping cough and tetanus, poliomyelitis and hepatitis A. Post-vaccination GBS is most likely to be accompanied by immune response directed against peripheral myelin. Surgical interventions, in which mechanical damage to the peripheral nerve causes the release of neuronal antigens and the response of the immune system to them, may be rarer causes of GBS. Furthermore, lymphoproliferative diseases, lymphoma in particular, enhance autoreactive T cells proliferation8. The autoimmune reaction results in nerve damage, demyelination, or functional nerve conduction block9.

The course depends on the trigger

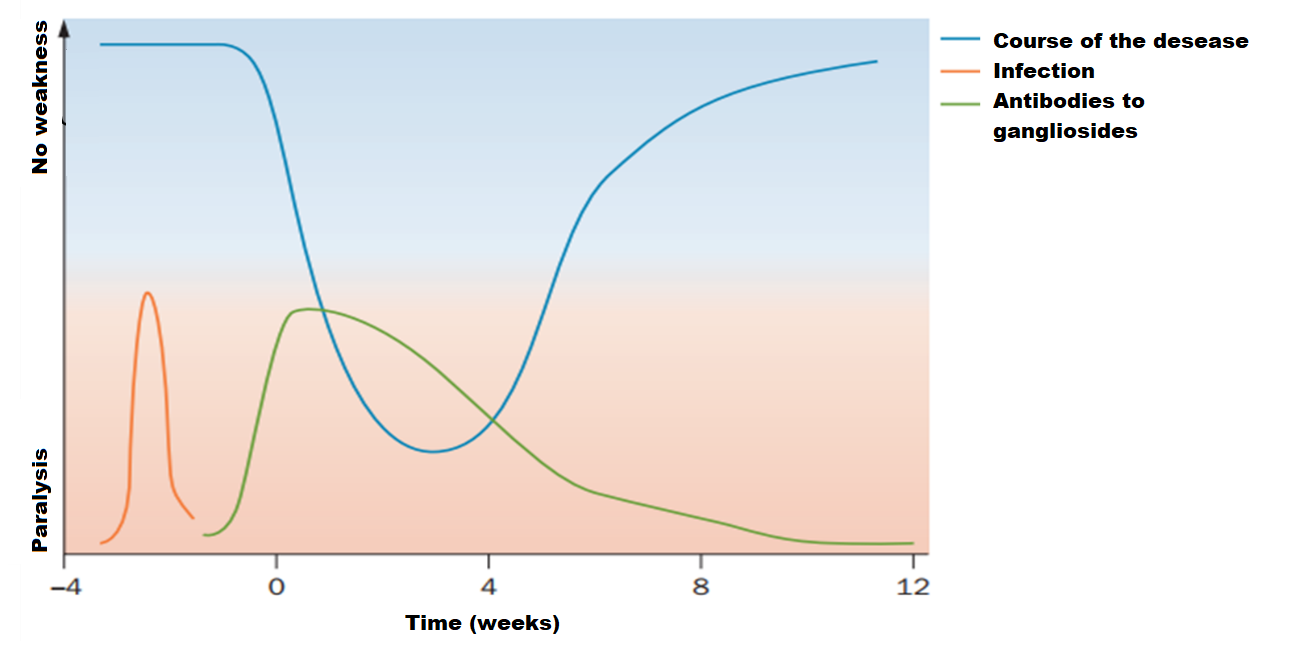

The typical course of the disease is sketched in Picture 1. Antiganglioside antibodies, which level decreases over time, can often be detected in patients at the onset of the disease. Symptoms increase and reach a maximum within 2-4 weeks. The recovery period can last from several weeks to months, and in some cases even years10.

Picture 1. Guillain-Barré syndrome typical course

The trigger launches an abnormal immune response, which leads to autoantibodies formation, that cross-react with neuronal gangliosides. This is enabled by molecular mimicry - a similar antigenic structure between the mucopolysaccharides of the pathogen and gangliosides of the peripheral nerve. The C. jejuni strain contains polysaccharides on its surface, which is similar to the carbohydrate moiety of peripheral nerve gangliosides. C. jejuni lipooligosaccharides induce the production of antibodies that cross-react with peripheral nerve gangliosides3. Antibodies that cross-react with various gangliosides have been repeatedly stated in patients with GBS 3,11-13.

However, only one subset of C. jejuni strains contain lipooligosaccharides that mimic the carbohydrate moiety of peripheral nerve gangliosides. The synthesis of these ganglioside-mimicking carbohydrate structures depends on a set of polymorphic genes and enzymes that vary greatly between different strains of C. jejuni14. The Thr51 variant of the C. jejunicst II gene, for example, is associated with GBS, while the Asn51 variant is associated with another demyelinating syndrome, Miller-Fisher (ophthalmoplegia, ataxia, and areflexia). This is due to the production of various antibodies that mimic to different sites of gangliosides.

Thus, specific antibodies associated with certain subtypes of GBS and specific neurological disorders have been found. For example, C. jejuni infections are typically associated with the AMAN or motor GBS subtype and show Gm1, GM1b, GD1a, or GalNAc-GD1a antibodies. And patients with Miller-Fischer syndrome often have antibodies against the gangliosides GD1b, GD3, GT1a and GQ1b, which are associated with ataxia and ophthalmoplegia3.

Read about the connection between viruses and GBS, vaccination and GBS in our next article.

References:

- Anil K. Jasti et al., Guillain-Barré syndrome: causes, immunopathogenic mechanisms and treatment. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2016, Nov; 12(11):1175-1189.

- Guillain-Barré syndrome. Clinical guidelines.

- Yuki, N. & Hartung, H. P. Guillain-Barré syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2012, Jun 14; 366(24):2294-2304.

- Emelin A.Yu. Guillain-Barré syndrome: recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Proceedings of the Russian Military Medical Academy. 2021; V. 40; 4: 51–57.

- Velichko I. A., Barabanova M. A. Guillain-Barré syndrome as an actual problem of neurology (literature review). Kuban Scientific Medical Bulletin. 2019; 26(2): 150–161.

- Anil K. Jasti et al., Guillain-Barré syndrome: causes, immunopathogenic mechanisms and treatment. Expert Review of Clinical Immunology. 2016, Nov; 12(11):1175-1189.

- Geurtsvankessel, C. H. et al. Hepatitis E and Guillain–Barré syndrome. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, Nov; 57(9):1369-70.

- Nankina I.V., Dunaevskaya G.N., Bembeeva R.Ts. Idiopathic inflammatory polyneuropathies in children. Attending doctor. 2008; 7: 24-27.

- Shang P, Zhu M, Wang Y, et al. Axonal variants of Guillain-Barré syndrome: an update. J Neurol; 268(7): 2402-2419.

- van den Berg B et al., Guillain–Barré syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014, Aug; 10(8):469-82. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.121.

- Willison, H. J. & Yuki, N. Peripheral neuropathies and anti-glycolipid antibodies. Brain. 2002; 125: 2591–2625.

- Kaida, K. & Kusunoki, S. Antibodies togangliosides and ganglioside complexes in Guillain-Barré syndrome and Fisher syndrome: mini-review. J. Neuroimmunol. 2010; 223: 5–12.

- Yuki, N. Guillain–Barré syndrome and antiganglioside antibodies: a clinician–scientist’s journey. Proc. Jpn Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2012; 88: 299–326.

- Gilbert, M. et al. The genetic bases for the variation in the lipo-oligosaccharide of the mucosal pathogen, Campylobacter jejuni. Biosynthesis of sialylated ganglioside mimics in the core oligosaccharide. J. Biol. Chem. 2002; 277: 327–337.

Colleagues, haven't you joined our PharmaCourses of MENA region Telegram chats yet?

In the chats of more than 6,000 participants, you can always discuss breaking news and difficult situations in a pharmacy or clinic with your colleagues. Places in the chats are limited, hurry up to get there.

Telegram chat for pharmacists of MENA region: https://t.me/joinchat/V1F38sTkrGnz8qHe

Telegram chat fo physicians of MENA region: https://t.me/joinchat/v_RlWGJw7LBhNGY0